Braille Capitalization: Rules & Best Practices For Beginners

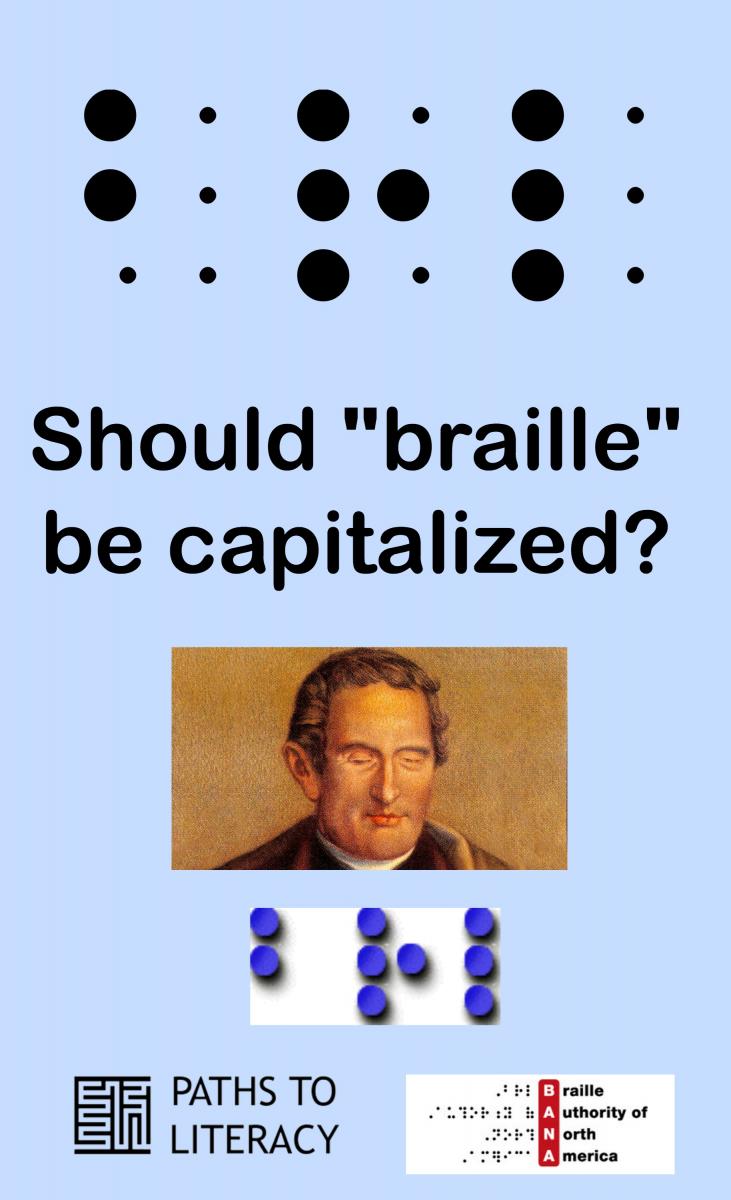

Should the word "braille" be capitalized? The answer, like the tactile writing system itself, is complex, nuanced, and ultimately a matter of context and established guidelines.

Braille, a system of raised dots representing letters, numbers, and punctuation, has revolutionized literacy for the blind and visually impaired. It's a tactile language adapted to hundreds of languages and dialects worldwide. Its origins trace back to Louis Braille, a French educator who, in the early 19th century, adapted a system of military code to create a more accessible method of reading and writing. But the question of how to write the word "braille" specifically, whether to capitalize it has sparked debate for years.

The initial impulse, understandably, was to capitalize "Braille" out of respect for its inventor. It's a common practice to capitalize words derived from proper nouns, such as "Newtonian" or "Shakespearean." However, over time, "braille" has become a widely recognized and commonplace word within the English language. It functions as a descriptive term for the code itself, akin to words like "alphabet" or "dictionary." This evolution has led to differing opinions, primarily between those who favor capitalization and those who advocate for lowercase.

The debate surrounding capitalization is particularly relevant for those learning and teaching braille. Educators need to understand the accepted norms to accurately transcribe materials and ensure that students, who are braille readers, are familiar with the correct formatting. Similarly, anyone creating braille signage or documents must navigate the stylistic guidelines to maintain consistency and clarity. The usage also extends to digital contexts, where accessibility is critical. For example, the practice of capitalising or not is pertinent in teaching the transition from formats like EBAE (English Braille American Edition) to UEB (Unified English Braille).

Adding to the challenge, various style guides and authorities offer conflicting recommendations. The Braille Authority of North America (BANA) recommends a lowercase "braille" when referring to the code itself, while the word is capitalized when it refers to Louis Braille as a person. The word "Braille" is also capitalized when it refers to product names like "Braille 'n' Speak", or book titles like "The Rules of Unified English Braille". The capitalization is a matter of stylistic choice.

Here's a table summarizing the key considerations concerning the capitalization of "braille":

| Aspect | Guideline | Rationale | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Referring to the Code | Lowercase "braille" | Treating it as a common noun for the writing system. | "She learned to read braille." "The braille code uses dots to represent letters." |

| Referring to Louis Braille | Capitalized "Braille" | Honoring the inventor as a proper noun. | "The life of Braille is a story of perseverance." |

| Referring to product names or book titles | Capitalized "Braille" | Respecting brand/title usage | "I use the 'Braille 'n' Speak'" |

| In sentences | Follow standard capitalization rules (first word of sentence, etc.) | Standard rules of written English | "Braille is a vital tool for literacy." |

The rules of capitalization are only part of the story. In braille itself, the system uses a different approach to indicate capitalization. Capital letters are indicated with a specific "capitalization indicator" (dot 6) placed before the letter to be capitalized, and a double capital sign is used to capitalize the whole word. There's no separate alphabet of capital letters. This system adds another layer of consideration for transcribers. The ability to accurately transcribe braille hinges on the transcriber's understanding of the capitalization conventions, contraction rules, and other formatting guidelines. This is especially important in ensuring that all materials are accessible to braille readers.

The guidelines extend beyond capitalization to other areas, such as the use of contractions. In braille, contractions are shorthand symbols that represent words or parts of words, contributing to faster reading speeds. However, when letters within a word are emphasized, for instance, through italics or bolding, the rules dictate that contractions should be avoided. Similarly, hyphens are not inserted unless they are found in the original printed text. These kinds of decisions play a part in making braille accessible for those who need it.

The ongoing debate about capitalizing "braille" underlines the dynamic nature of language and how it adapts to new technologies and users. While there may not be a single definitive answer, awareness of the various guidelines and the rationale behind them is key. Whether an individual chooses to capitalize "braille" depends on their personal preference or the particular style guide they are following. Nevertheless, understanding these guidelines allows for the creation of materials that are both accurate and accessible.

The nuances in braille's capitalization rules, as well as the use of contractions and other elements, reflect how the system is carefully adapted to communicate information. This system, developed by Louis Braille, and later adapted to many languages and dialects worldwide, continues to be a cornerstone of literacy. The commitment to accessibility, accuracy, and clarity remains paramount.

For more details on the proper use of "braille" and the guidelines set by BANA, and the evolving best practices, you can also view the position statements and resources made available on their website. This will give you a much deeper understanding of the subject, the guidelines and recommendations on the topic.

Ultimately, the key is to be consistent and to prioritize clarity. The goal is to provide accurate and easily understandable braille materials for the blind and visually impaired.